Somebody probably hates you right now, no matter how nice you think you are.

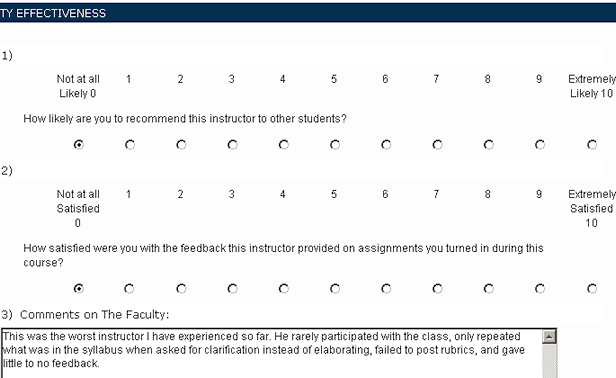

I was recently reviewing evaluations I received for an online course I taught. Two strikingly different evaluations happened to be consecutive in the list. Here’s the first:

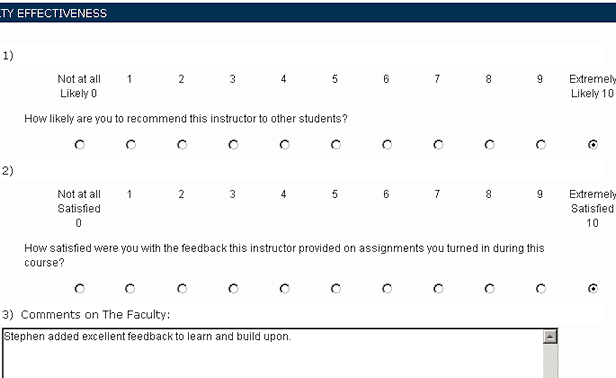

Yowza! I must be awful. However, apparently not in everybody’s mind, because here’s the second:

As it turns out, across the 8 evaluations I received, my average grade was an 8, and my median grade was a 9. So, most folks thought I was half-decent, but that one camper was definitely not happy with me.

Here’s my speculation – I pissed that person off somehow. If I had just been not-so-good, I wouldn’t have received the zeros or the scathing commentary. I would have instead gotten poor-ish grades and inspired maybe a sentence about how I’m not worth the student’s hard-earned tuition dollars. A zero, however, is a revenge grade – a totally different ballpark.

Here’s the scary thing – I have no idea why anybody in that class would have given me that grade. I don’t remember any significant conflicts with anybody. As I recall, I was fairly easygoing, and nobody did particularly poorly. Yet, at some point, something I said or did drove this person into a fury, and they vented using the only weapon at their disposal. While the specific mark was engulfed by the numbers surrounding it, its lesson is indelible: sooner or later, we are bound to make somebody around us fuming mad for reasons that are totally mysterious to us. It follows that the people at whom we fume may not always know why we are angry. Your arch-nemesis may think of you as that grumpy person who doesn’t ever say hello.

We experience each other as facets, particularly when we have only limited interactions. It’s hard, maybe pointless, for anybody to fret over all of their facets. Better to aim for a high average and get comfortable with the idea of an occasional zero.