Today I’ll be giving a talk on SQL injection at SecureWorld Expo (Philadelphia). My presentation is attached for attendees (and other interested parties) to reference.

Category Archives: Code

SQL Injection Talk at (ISC)2 Security Congress

In September, I was a featured speaker at the (ISC)2 Security Congress, where I gave a talk on SQL Injection. A few attendees and others have asked me to make the video and slides available for download – consider it done.

Shared Technology and Ease of Integration

A shared set of technologies implies very little about how easy it will be to integrate two products.

In a past organization (of course, tales of foolishness are never explicitly set in one’s present organization), we were in the midst of a multi-year effort to build THE SYSTEM, which would replace 639 other systems, save a zillion dollars, unify the thirteen colonies, and restore balance to the Force.

In spite of (or maybe as a consequence of) its inestimable virtues, THE SYSTEM (hereafter “TS”) was taking a long honking time to build. As fate would have it, my corner of the organization had a semi-urgent need for a planned part of TS, but that part was not scheduled to be delivered for another two years. Unable to persuade the makers of TS to accelerate development of the piece we needed, multiple persons in my organization became afflicted with the idea that my development group could assume responsibility for building that one chunk of TS ourselves, on a timeline more congenial to our needs.

One person sold the concept thusly – since TS was being developed in Java, if we were to write our version of the sorely needed piece in Java, then said piece could easily be grafted onto the rest of TS when the time came. This strategy would allow us to get what we needed sooner, and would save the makers of TS time, because we would have implemented a significant feature for them, and all they would need to do is integrate it. They key to all of this was that we would build on the same platform (Java), so as to make integration of the two efforts relatively easy to achieve.

That’s a lot like saying that two documents can be easily merged together because both are written in English .

The truth is that a shared technical platform doesn’t buy you very much if you need to integrate two independently developed pieces of software. In fact, it may be a liability of sorts. If I’m trying to incorporate the capabilities of a Ruby application into a C# application, everybody recognizes that I’m going to have to rewrite the Ruby stuff. However, if I’m trying to incorporate one Java application into another, independently developed application, I’m still going to have to rewrite lots of stuff, and the shared platform may actually hurt me insofar as it leads people to assume otherwise.

Like two documents, two independently developed applications may share a common language, but will inevitably differ in goals, style, assumptions, and overall organization. These differences will not be abstracted and isolated in particular places, but will be suffused throughout the code of each in ways that are difficult to systematically identify, let alone tease out.

Although the object-orientation of a language like Java does go some way toward making an application more like a set of modular and reusable components, this capacity is often over-emphasized. The promise of a set of objects that faithfully model the real world and hence transcend problem-specific solutions is usually illusory. There is often no “real world” to be seen outside of some contextual problem space, as the problem space itself heavily colors designers’ perceptions of what the world to be modeled looks like. Designers solving different problems within what is in principle the same domain will inevitably see the domain in terms of the problem, and hence will model different worlds. As such, when it comes time to integrate their code, there will be no conceptual lingua franca to complement the syntax of their shared implementation language, making it virtually impossible to combine the two codebases without either substantially rewriting one or creating some huge integration layer that exists mainly to bridge the conceptual divide.

A shared language doesn’t get you very far, especially not in a world where most technologies can now talk to each other through XML. Even if you start with a shared development language, differences in goals, styles, assumptions and organization will mitigate strongly against the ability to integrate any two codebases without significant rework, unless those codebases were intentionally designed to be integrated in the first place.

What Between Means in SQL (Not What You’d Think)

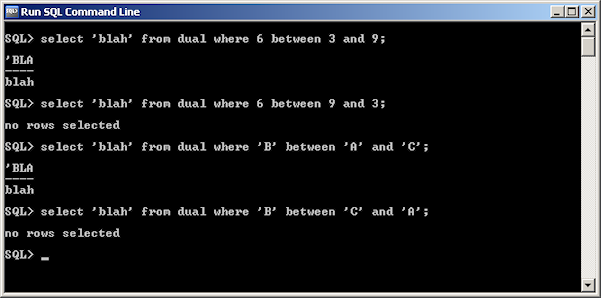

In SQL, “BETWEEN X AND Y” means “greater than or equal to X and less than or equal to Y” – not necessarily what you might infer from its plain-English counterpart.

Is 6 between 3 and 9? Yes.

Is 6 between 9 and 3? Yes, but not in SQL.

In SQL, we use the BETWEEN operator to determine whether a value falls between two other values. We might think that using a clause like “BETWEEN X AND Y” establishes a range between X and Y, and that value comparisons will be true as long as the value being compared falls into that range.

However, the BETWEEN operator works differently. “BETWEEN X AND Y” actually translates into “greater than or equal to X and less than or equal to Y.” This means that X and Y have to be placed in ascending order for the statement to work correctly – X must be the lower of the two values.

Here’s a screenshot demonstrating this in Oracle, but virtually any database works the same way. I’ve included examples for both numbers and characters.

Usually, this behavior isn’t a problem. Especially if you are working with literals, as in the screenshot above, you’re likely to put the lower value first, just as a matter of habit. However, if you are performing logic based on variables or column values, you need to make sure that the BETWEEN clause gets the lower end of the range first, or else your results may not be what you expect.

Setting Focus Without Interrupting User Typing

Don’t set focus if the user has already been where you’re going to send them.

Many websites and web applications will set focus on page load, moving the cursor to some point at which it is presumed the user will want to start typing. This is especially common for search pages and login screens, and generally sensible in these contexts. However, developers should recognize that setting focus can be disruptive to users, and code intended to set focus should be made smart enough to detect when this would be inappropriate.

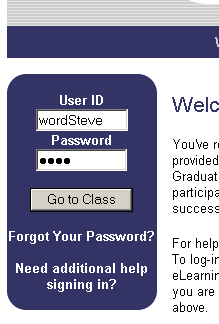

Above is an example of a typical login form, with fields for username and password. The designers of this site decided that they would set focus in the User Id field as soon as the page loaded, since most users are likely to want to login at this point. To do so, they implemented the following Javascript, called from the onLoad event of the <body> tag:

Above is an example of a typical login form, with fields for username and password. The designers of this site decided that they would set focus in the User Id field as soon as the page loaded, since most users are likely to want to login at this point. To do so, they implemented the following Javascript, called from the onLoad event of the <body> tag:

function setfocus(){

if (document.forms[0]) {

document.forms[0].elements[0].focus();

}

}

In principle, this is a reasonable choice. However, the code is not sophisticated enough to take into account a plausible scenario. Sometimes, if the page takes a while to load, the login form will become visible and available to users before the full page renders and onLoad is fired. Let’s imagine a case in which a user named Steve with a password of password is logging in.

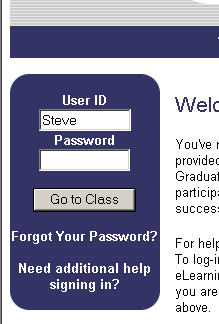

We’ll assume that Steve begins to login before the page has completely loaded. He is able to type his full username into the appropriate field, and then tab to the password field, all before the page has finished and the onLoad can be fired. (For complex or otherwise slow sites, this is not implausible, even on a broadband connection. It has happened to me many times on the site in question.) He then starts typing out his password. Suddenly, while he is in the midst of typing the password, the page finishes and onLoad fires, with the called function dutifully setting focus back to the User Id field. He continues typing for a moment or two, not recognizing what has happened, and then realizes that half of his password is plainly visible in the User Id field, smashed onto the front of his username in an ungainly manner:

We’ll assume that Steve begins to login before the page has completely loaded. He is able to type his full username into the appropriate field, and then tab to the password field, all before the page has finished and the onLoad can be fired. (For complex or otherwise slow sites, this is not implausible, even on a broadband connection. It has happened to me many times on the site in question.) He then starts typing out his password. Suddenly, while he is in the midst of typing the password, the page finishes and onLoad fires, with the called function dutifully setting focus back to the User Id field. He continues typing for a moment or two, not recognizing what has happened, and then realizes that half of his password is plainly visible in the User Id field, smashed onto the front of his username in an ungainly manner:

While this is only a minor irritation from a usability perspective, it has potentially significant security implications if it happens while the wrong people are watching. A better way would be to make the code a litle more intelligent, and have it set focus only if the target field has not yet been altered by the user, along the lines of something like this:

function setFocus(){

if (document.forms[0]) {

if (document.forms[0].elements[0].value=='') {

document .forms[0].elements[0].focus();

}

}

}

Of course, you might want to skip the home-grown Javascript and do this sort of thing in jQuery, but no matter how you roll it, the principle is the same – if the user has already started to enter text in a field, then don’t set focus there because of an onLoad event. You’re more likely to be interrupting than assisting.